“You can come by the office any time from 8 a.m. onward. My assistant will give you a copy of your daughter’s medical file. Dr. Marcotte and the pneumology team will see you tomorrow at 1 p.m. at Sainte-Justine. She’ll be admitted for a week, maybe longer.”

That’s how the pediatrician let me know, in so many words, that something was wrong with my little girl. It’s never a good sign when they ask both parents to come in for an appointment.

The next day, there we were, on our way to the city. Camille slept in her car seat the whole way, her back facing the road ahead. It was an eerily quiet trip. Tears of uncertainty streamed down my cheeks.

Coming through the revolving doors at Sainte-Justine with my baby and luggage in tow, I held out hope that this was all one big mistake. Like thousands of parents just like me do every year. Sometimes they are in and out just long enough to have a story to tell. Other times, they have chronic problems to contend with.

That was a long time ago, but it still feels like yesterday. And tomorrow, in some respects.

A few tests later, the doctor gave us a diagnosis that no parent ever wants to get. The kind of news that makes you feel like your legs will give out and you’ve just been punched in the gut. Cystic fibrosis. A potentially life-threatening disease without a cure. A severe genetic mutation. A multidisciplinary clinic. Ongoing follow-up with Sainte-Justine through to adulthood. Treatments. Research. Hope.

But unlike boxers who have trained for their time in the ring, we were taken completely off-guard and fighting blind. With this one announcement, I realized that my life, and my dreams for my daughter’s future, would never be the same.

What awaited my beautiful blonde, blue-eyed girl was a childhood surrounded by all sorts of specialists. Her life expectancy, which even now is shorter than my own, and her very fate was in their hands.

There was the young pharmacist, just out of school, who had lots to offer up in terms of how to proceed. An uncommonly bright and inquisitive medical fellow. A veteran social worker whose calm and composure helped steel our resolve. The nutritionist who boosted my morale with information from scientific studies. The confident team of doctors citing promising statistics. And a flurry of experts who consulted on her case. They all adopted Camille as their own.

« Instead of digging in my heels and trying to take over or throwing up my hands in despair, I fell back on them for support. It was such a relief. I could feel that Camille’s childhood was in very good hands. »

The back-and-forth to the hospital became part of our routine. With each successive candle on her birthday cake came additional hospital stays. We were never quite sure where this degenerative disorder would take her next.

“Your job as a parent is to make her life as normal as possible and treat her like any other child her age,” we were told. I tucked this precious piece of advice away for future reference. Beyond anything else, Camille needed to be a kid, first and foremost. That was my mission. Despite the differences between her “normal” at Sainte-Justine — her second family — and that of her peer group.

Camille took her first steps between two chairs in a waiting room. Her first words were uttered pointing at the animals on the wall of a clinic hallway. The height of her terrible twos was her refusal to take her coat off in the Test Centre. Her favourite dessert was the chocolate pudding in the cafeteria.

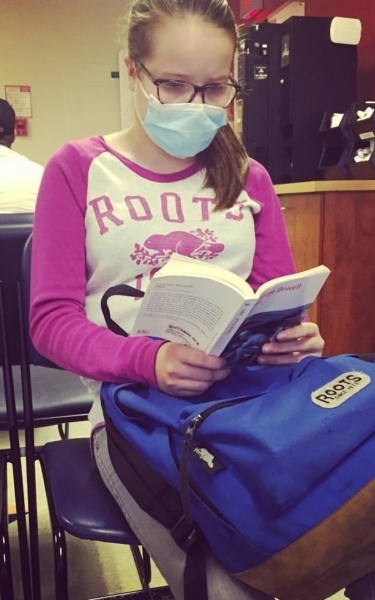

She loved to give her best drawings to the doctors. I would always strategically time some surprises to coincide with the end of a medical procedure. A Grade 4 reading assignment was done between an X-ray and a lung function test. Any time she would act up, whether or not she had a hospital bracelet on her wrist, my furrowed brow would set her straight.

We got to know every square inch of these hallways. Camille knew her way around like a professional tour guide. And more than a few Christmas celebrations were marked by the smell of alcohol swabs.

And as she grew, so did Sainte-Justine.

I remember one particular stay when she was having trouble breathing. I asked her how she was feeling.

Her answer, “I’m fine, mom, it’s my lungs that are the problem.”

That’s when I realized that she saw herself as something more than her illness and her fragile little body. I guess I managed to follow the good advice I was given after all.

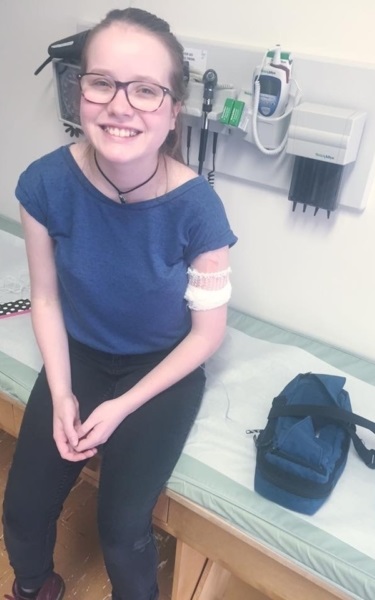

I saw her in pain plenty of times. I winced as I felt it too. When she reached her teen years, she rebelled, as expected. The unfairness of being different struck her hard at that age. I can’t say I didn’t sympathize. As a parent, it was tricky keeping everything afloat.

Over the years, we welcomed new caregivers to the team — people who would come up against the worst that life has to offer, who would spend the better parts of their adult lives between these four walls.

How many times, driving out of the parking garage after visiting hours were over, did I wipe a tear from my face as I left Camille behind, torn between her and her brothers. How many bags did I pack and unpack for the hospital? Still, I was determined to make her life as normal as I could.

Flash forward to today: Camille is now 20 years old. Her childhood is peppered with memories of Sainte-Justine. Here is where she built her most enduring friendships and connected with countless mentors. So many influential and reassuring encounters, interspersed with so many moments of pain and suffering.

The statistics proved right: she reached adulthood and was referred to an adult care clinic. Dr. Jacques-Edouard Marcotte, who initially admitted her into Sainte-Justine, is the one who signed her transfer papers to the CHUM. Our social worker, who has since passed away, shared this with me. “At the beginning of my career, our cystic fibrosis clinic provided one thing: palliative care. But your daughter will probably attend university.” She was right. Camille won the first round of her battle. She will be starting her undergraduate program in January. And that’s because of the research, the outstanding care of everyone at Sainte-Justine and the donors who have been there every step of the way.

« When she turned 18 and exited the revolving doors one last time, other parents were coming through on their way in, with the same fear that shook me to the core all those years ago. Same may have later left with a heavy heart. Every story is different. »

And I was right behind them, as I took up my new duties working at the CHU Sainte-Justine Foundation. The Foundation’s mission to support Sainte-Justine’s work resonated deeply with me. I wanted to do my best to give back, so that each professional, each doctor and each researcher has what they need to support parents who feel lost, like I once did. So they can help each young patient keep smiling and keep being a kid — and make sure every family feels loved and cared for. So they can continue to deliver their services with conviction and passion.

By choosing to work for Sainte-Justine, I am helping to support this village that is so important in countering the suffering and injustice that strike in these early years.

This village is one where every parent can connect with professionals who are unequalled in their field, where every child is fortunate to receive top-of-the-line services from top-of-the-line experts.

Sainte-Justine is a village that does more than provide patient care: they provide comfort and compassion. And that’s in large part because of the donors who contribute to the Foundation. Every gift helps give families peace of mind. And I think that’s the best and most powerful thing that a charity can accomplish.

Sainte-Justine was there for us in the past and will continue to be there for others in the years to come. Stronger than ever. And with a human touch that makes all the difference.

Véronique Papineau